Overview

The first chapters of Chronicles challenge the endurance of most modern readers. At first glance, we are tempted to pass over these ancient lists and genealogies as irrelevant, but our stance toward these chapters does not match the Chronicler's outlook. He began his history with these materials to answer critical questions raised by the experience of post-exilic Israel. Who are the people of God? What privileges and responsibilities do they have? The Chronicler's answers to these questions revealed many important themes which characterize his entire history.

Israel's royal history, exile, and continuing troubles after the exile created a crisis of identity for many Israelites. In 922 B.C. the northern tribes broke away from Judah to establish their own monarchy and worship centers (see 2 Chr 10:16-19; 1 Kgs 12:16-33). Their sins were so great that the Lord sent the Assyrians to destroy the northern kingdom and to carry many of its citizens into exile in c 722 B.C. (see 1 Chr 5:25,26; 2 Kgs 17:6-23). The Chronicler's original readers wondered about these events. Were these scattered tribes still to be counted among the people of God? What place did they hold in God's plan?

In the decades that followed the fall of northern Israel, the people of Judah also fell into flagrant disbelief. Consequently, the Lord sent the Babylonians to destroy Jerusalem in 586 B.C. and countless Judahites also went away into exile (see 1 Chr 9:1b; 2 Chr 36:17-21; 2 Kgs 25:1-12). The Chronicler's readers faced a serious crisis. Had God forsaken Judah as well?

Even during the exile controversy grew between different groups of Israelites (see Ezek 11:14-25). Those left in the land believed they were the rightful heirs of God's blessings. Those taken to Babylon argued they were the true people of God. This controversy became very practical for the Chronicler's post-exilic readers. In 538 B.C. the Persian emperor, Cyrus, permitted the exiles to return to Jerusalem (see 2 Chr 36:22-23; Ezra 1:1-4), but critical questions still had to be settled. Who had a legitimate claim to God's blessings?

What responsibilities did the various groups have? Overview; and The Roots of Israel. In his genealogies and lists the Chronicler answered these and similar questions. In response to controversy and confusion in the post-exilic community, he gave an account of the identity, privileges, and responsibilities of God's people.

The book of Chronicles begins with nine chapters of genealogies. When we think of modern genealogies, we often picture a family tree containing the names of every family member. Genealogies in biblical times, however, were different from our modern genealogies. They followed a variety of forms and served many different functions. These variations also appear in the Chronicler's extensive use of genealogies.

The Chronicler's genealogies take on several forms. Some passages are linear and trace a single family line through many generations (e.g., 1 Chr 2:34-41); other genealogies are segmented and sketch several family lines together (e.g., 1 Chr 6:1-3). The Chronicler also omitted generations without notice, mentioning persons and events that were important to his concerns. In these cases, the expression "son of" actually meant "descendant of" and "father of" meant "ancestor of" (e.g., 1 Chr 6:4-15). Beyond this, just as ancient genealogies often included brief narratives highlighting significant events, the Chronicler paused on occasion to tell a story (e.g. 1 Chr 4:9-10; 5:18-22).

The functions of ancient genealogies also varied. They not only sketched familial relations, but political, geographical, and other social connections. In many cases, the expressions "son of" and "father of" had a broader meaning than immediate biological descent. In line with these ancient functions of genealogies, the Chronicler gave an assortment of lists, including families (e.g., 1 Chr 3:17-24), political relations (e.g., 1 Chr 2:24,42,45,49-52), and trade guilds (e.g., 1 Chr 4:14,21-23).

Structure

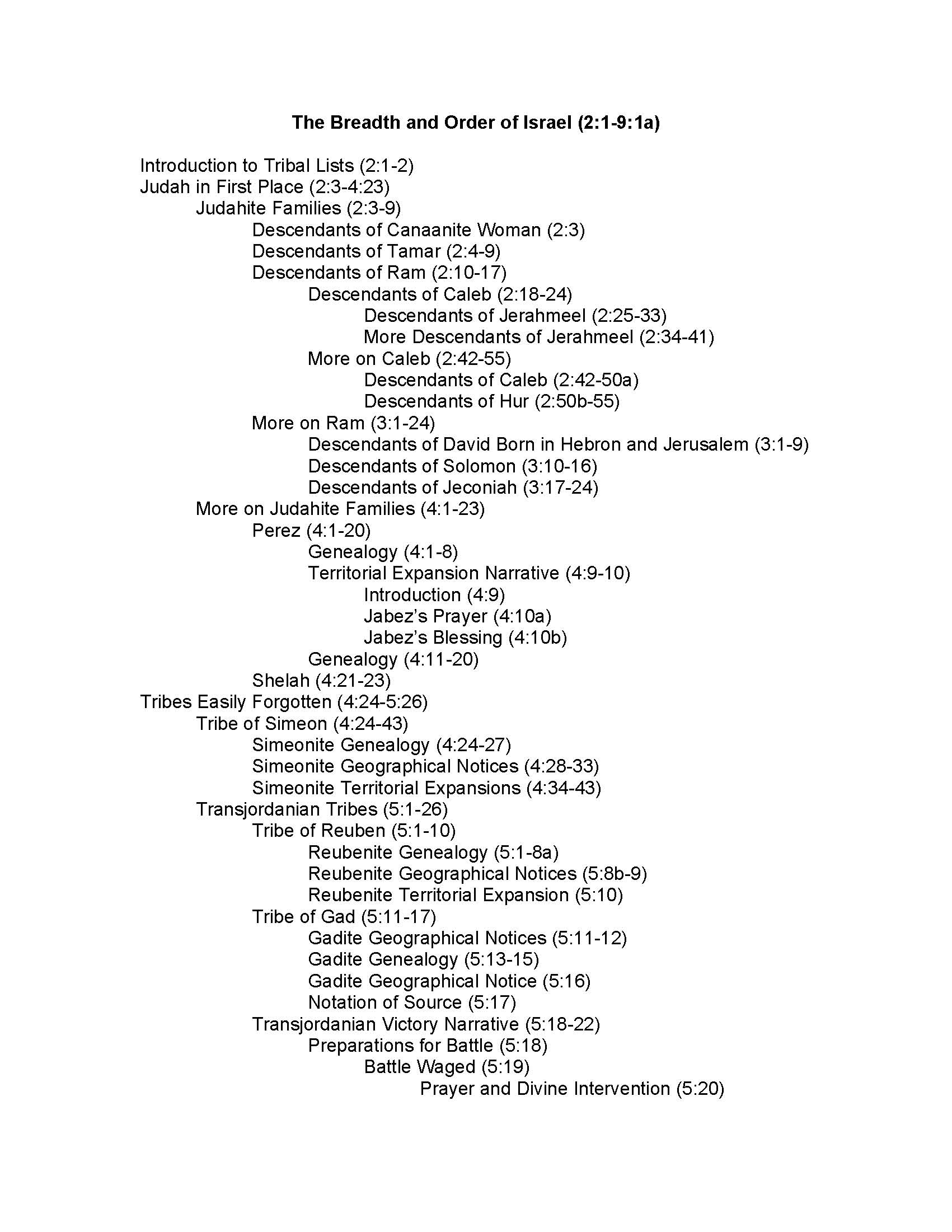

The Chronicler's record divides into three main sections (see figure 4). The symmetry of this presentation is evident. In the large center of these chapters the Chronicler focused on the breadth and order of the tribes of Israel (2:1-9:1a). As a prelude to this crucial material he quickly summarized the historical roots of Israel by noting the special ancestors of the twelve tribes (1:1-2:2). He then closed this portion of his book with a brief account of the descendants of the twelve tribes who stood at the center of the early post-exilic community (9:1b-34).

The Roots of Israel (1:1-2:2)

The first task before the Chronicler was to establish that his readers were descendants of a divinely selected people. To accomplish this end he drew from several chapters in Genesis to demonstrate that God had chosen the twelve tribes of Israel for special privileges and responsibilities which now belonged to his readers.

Structure

The Chronicler's account of Israel's roots divides into three main sections (see figure 5). The people of Israel were not like other nations; they were beneficiaries of a divine program of narrowing selection. From all of Adam's descendants, Noah was selected as God's favored man. From all of Noah's descendants, Shem stood in special relationship with

God. From all of Shem's descendants, God selected Abraham. From all the descendants of Abraham, Isaac was chosen. From the descendants of Isaac, God chose Israel and his children. The history of humanity from Adam to Jacob proved that God had selected Israel to be his special people. The post-exilic readers of Chronicles had faced discouragements that caused many of them to wonder if God had utterly rejected them. By tracing the special roots of Israel, the Chronicler demonstrated that Israel held a privileged relationship with the Creator.

Descendants of Adam (1:1-3)

By beginning his record with Adam to Noah (1:1-3), the Chronicler tied the people of God in his day to biblical primeval history (see Gen 1:1-11:9). As children of Adam Israel had common origins with the entire human race. They were recipients of Adam's blessing and curse like all other peoples (see Gen 1:26-29; 3:15-24; Rom 5:12-21). The names that follow Adam, however, indicate that a narrowing process of divine election was already at work in the earliest stages of human history. God chose to show special favor only to the line of Seth and Noah (1:1-3). While other primeval people rebelled against their Creator, the book of Genesis characterized these men as the first who "called on the name of the Lord" (Gen 4:26). They received the blessing of long life (see Gen 5:5,8,11) and Noah alone was chosen to survive the flood (see Gen 6:8-9,17-18). The Chronicler's readers knew the biblical records of these primeval figures. Their mere mention as ancestors of the tribes of Israel made it evident that Israel was not an ordinary nation; her roots stretched from the most honored figures of primeval history.

Descendants of Noah (1:4-27)

The sons of Noah first appear here in the order of Shem, Ham, and Japheth (1:4), as they occur in Gen 5:32. After introducing their names, however, the Chronicler reversed the order of Noah's sons to end with Shem (Japheth [1:5-7], Ham [1:8-16], Shem [1:17-27]), the ancestor of Israel. As on several other occasions, the Chronicler reversed the traditional order of the names to end with the man whom God specially blessed (see 1:34a; 2:1-2). God favored the Shemites, or Semitic peoples, more than all other nations on earth. As Genesis 9:25-27 indicates, God promised that the Shemites would conquer the Canaanite descendants of Ham and provide blessings for the descendants of Japheth.

Nevertheless, God's favor did not extend equally to all Shemites. It was directed toward one special descendent of Shem, Abram (1:27). Abram was the father of the tribes of Israel; he became the heir of the privileges granted to Shem and the conduit of these blessings to the nation which he fathered (see Gen 12:1-3).

Descendants of Abraham (1:28-34a)

The Chronicler turned next to the sons of Abraham to distinguish the chosen seed from Abraham's other descendants (1:28-34a). First, he mentioned Isaac and then Ishmael (1:28), but he reversed the order again by first listing the descendants of Ishmael (1:29-31), the father of the Arab nations, and the sons of Keturah, Abraham's second wife (1:32-33). This change of order indicated that only the descendants of Isaac (1:34) could rightfully claim Abraham's blessing (see 1:17-27; 2:1-2).

Isaac was the only child of Abraham born by divine promise instead of human design (see Gen 17:15-21; 18:9-15; 21:1-8; Gal 3:15-18,26-29). Isaac's supernatural birth reminded the Chronicler's readers that they were not like the other descendants of Abraham. Their heritage rested on Abraham's faith in God's promises, not in ordinary familial lineage (see Rom 4:16-21).

Descendants of Isaac (1:34b-2:2)

The final step in the Chronicler's narrowing definition of God's people focuses on the sons of Isaac (1:34b-2:2). In usual fashion, the chosen line appears last (see 1:17-27,34a). The text deals first with Esau (1:35-54) who sold his birthright to Jacob (see Gen 25:27-34). Then it speaks of the sons of Israel (2:1-2) who inherited God's promises to Abraham. The final verses in the record of Isaac's descendants (2:1-2) serve a literary function often called the "Janus effect." They function as the end of this material (1:34b-2:2), but they also introduce the passages that follow (2:1-9:1a).

In this context, the twelve tribes are explicitly identified as descendants of Isaac's son, Israel (2:1). The blessings of God came through the man Israel, but Genesis does not hide his imperfections (see Gen 25:27-34; 27:1-36; 30:41-43; 31:20-21). Early in his life Jacob lived up to the meaning of his name, "the supplanter" (see Gen 25:26; 27:36). As God changed his character, however, he received the honorable name Israel, "because you have striven with God and men and have overcome" (Gen 32:28). Jacob cherished the birthright of Abraham and did all he could to acquire it.

By mentioning all twelve tribes of the nation Israel, the Chronicler reached the high point of this portion of his genealogies. His main purpose for the preceding material was to provide a reminder of the origins of the tribes. From his perspective, the post-exilic readers enjoyed a remarkable heritage of blessings and privileges.

The Breadth and Order of Israel (2:1-9:1a)

Having reminded the readers of their connection to the early people of God, the text turns next to lengthy records of the tribes of Israel. Comparisons with other biblical accounts reveal great selectivity in this material. These selections emphasize two important theological concerns. First, the breadth of God's people demonstrates that the privileges of divine election belonged not to a few but to all the tribes of the nation. Second, some tribes receive more honor than others. These accounts highlight certain groups who played important roles in national life before and after the exile.

Structure

The Chronicler' record of the tribes of Israel divides into five main parts which are enclosed by an introduction and summation (see figure 6).

Two general comments should be made about the arrangement of these genealogies. First, although they point to the breadth of God's people, these lists do not mention the tribes of Dan and Zebulun. The brevity and awkward Hebrew grammar of Naphtali's record (see 7:13) may indicate that the Chronicler's original text included a longer account of Naphtali as well as Dan and Zebulun. These materials may have been lost through transmission errors,but this explanation is uncertain (see Introduction: Translation and Transmission). The Chronicler himself may have omitted these tribes for other unknown reasons. Even so, the complete list of Jacob's sons in 2:1-2 shows that these chapters express the Chronicler's insistence that all the tribes be counted among the people o God (see Introduction: 1) All Israel). Earlier prophets had already indicated that the restoration after exile would involve all twelve tribes (see Isa 9:1-7; 11:12; 27:6,12-13; 43:1-7; 44:1-5,21-28; 49:5-7,14-21; 59:20; 65:9; 66:20; Ezek 34:23-24; 37; 40-48; Hos 1:11; 3:4-5; Amos 9:11-15; Mic 2:12-13; 4:6-8; 5:1-5a). The Chronicler also looked for a reunification of all Israel. From his point of view, the post-exilic restoration would remain incomplete until representatives of all the tribes were gathered in the promised land (see Introduction: 1) All Israel).

Second, the relative distribution of verses covering the tribes provides another important insight to the Chronicler's purposes. He alternated between long and short accounts (see figure 7). After an introduction (2:1-2), he began with a long text on Judah (2:3-4:23).

This Judahite record precedes the relatively short records of Simeon (4:24-43) and the tribes who lived east of the Jordan River (5:1-26). Then another lengthy passage focuses on the sons of Levi (6:1-81), just before six short genealogies (Issachar ... Asher [7:1-40]). Finally, a relatively long account of Benjamin (8:1-40) closes the material.

These uneven distributions suggest that the Chronicler honored Judah, Levi, and Benjamin more than the other tribes. What did these three tribes have in common that warranted this honored status? Throughout history a great number of Judahites, Benjamites, and Levites remained committed to the Davidic king and the Jerusalem temple. Kingship and temple were the two essential institutions in the Chronicler's ideal for restored Israel (see Introduction: 4-9) King and Temple). Judah, Levi, and Benjamin probably held extraordinary positions in the Chronicler's view because of their past loyalties to these institutions. As such, these tribes also played vital roles in the restoration efforts of post-exilic Israel. The last portion of the Chronicler's genealogies (9:1b-34) confirms this understanding of his purpose.

In this description of the early returnees he once again emphasized the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, and Levi by drawing attention to their large numbers (see figure 7).

Introduction to Tribal Lists (2:1-2)

As mentioned above, these verses serve a double function. They close out the previous section of God's narrowing election (see 1:1-2:2), but they also introduce the following chapters which focus on the breadth and order of God's people (2:1-8:40). The heads of Israel's twelve tribes appear in the order of Gen 35:23-26 with the exception of Dan's placement. The Chronicler began with this list to acknowledge that all the tribes without exception were to be accepted as the heirs of Israel's blessing. This opening list balances with the closure of 9:1a (see figure 6).